-

PROMETHEUS BOUND

-

A summary and analysis of the play by Aeschylus

-

-

| This document was originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 1. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 70-78. |

-

Purchase Prometheus Bound

-

-

|

-

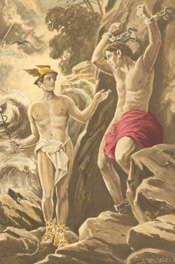

PROMETHEUS BOUND

-

An original painting by A. Russell

|

|

|

The Prometheus Bound stands midway between Prometheus the Fire-giver and Prometheus Unbound. In grandeur of conception and imagery it has never been surpassed, not even in the works of Shakespeare, for here is the very essence of tragedy, her inmost spirit revealed in its sternest mood, in all its prostrating and annihilating force. The subject of the first play is the transgression of Prometheus, who brings fire to mankind, whereby they become no better, and confers on them other benefits, as he himself relates to the chorus when bound to the rocks. From love of mortals he roused their reason; he taught them to make dwellings, showed them the stars, the use of number and writing--mother of the Muses. He tamed horses and built ships, taught the virtues of healing potions, the various modes of divination, and how to turn to account things dug out of the earth. He it was who taught mortals all they know.

To the chorus of sea-nymphs Prometheus thus relates what he has done for mankind:

|

|

-

- Think not it is through pride or stiff self-will

- That I am silent. But my heart is worn,

- Self-contemplating, as I see myself

- Thus outraged. Yet what other hand than mine

- Gave these young gods in fulness all their gifts?

- But these I speak not of; for I should tell

- To you that know them. But those woes of men,

- List ye to them, how they, before as babes,

- By me were roused to reason, taught to think;

- And this I say, not finding fault with men,

- But showing my good-will in all I gave.

- For first, though seeing, all in vain they saw,

- And hearing, heard not rightly. But, like forms

- Of phantom-dreams, throughout their life's whole length

- They muddled all at random; did not know

- Houses of brick that catch the sunlight's warmth,

- Nor yet the work of carpentry. They dwelt

- In hollowed holes, like swarms of tiny ants,

- In sunless depths of caverns; and they had

- No certain signs of winter, nor of spring

- Flower-laden, nor of summer with her fruits;

- But without counsel faired their whole life long,

- Until I showed the risings of the stars,

- And settings hard to recognize. And I

- Found Number for them, chief device of all,

- Groupings of letters, Memory's handmaid that,

- And mother of the Muses. And I first

- Bound in the yoke wild steeds, submissive made,

- Or to the collar of men's limbs, that so

- They might in man's place bear his greatest toils;

- And horses trained to love the rein I yoked

- To chariots, glory of wealth's pride of state;

- Nor was it any one but I that found

- Sea-crossing, canvas-winged cars of ships:

- Such rare designs inventing (wretched me!)

- For mortal men, I yet have no device

- By which to free myself from this my woe.

-

- CHORUS.

- Foul shame thou sufferest: of thy sense bereaved,

- Thou errest greatly; and, like leech unskilled,

- Thou losest heart when smitten with disease,

- And know'st not how to find the remedies

- Wherewith to heal thine own soul's sicknesses.

-

- PROMETHEUS.

- Hearing what yet remains thou'lt wonder more,

- What arts and what resources I devised;

- And this the chief; if any one fell ill,

- There was no help for him, no healing food,

- Nor unguent, nor yet potion; but for want

- Of drugs they wasted, till I showed to them

- The blendings of all mild medicaments,

- Wherewith they ward the attacks of sickness sore.

- I gave them many modes of prophecy;

- And I first taught them what dreams needs must prove

- True visions, and made known the ominous sounds

- Full hard to know; and tokens by the way,

- And flights of taloned birds I clearly marked--

- Those on the right propitious to mankind,

- And those sinister--and what form of life

- They each maintain, and what their enmities

- Each with the other, and their loves and friendships;

- And of the inward parts the plumpness smooth,

- And with what color they the gods would please,

- And the streaked comeliness of gall and liver;

- And with burnt limbs enwrapt in fat, and chine,

- I led men on to art full difficult;

- And I gave eyes to omens drawn from fire

- Till then dim-visioned. So far then for this.

- And 'neath the earth the hidden boons for men,

- Bronze, iron, silver, gold, who else could say

- That he, ere I did, found them? None, I know,

- Unless he fain would babble idle words.

- In one short word, then, learn the truth condensed--

- All arts of mortals from Prometheus spring.

After his victory over the Titans, Zeus had determined to destroy the human race and create a new and better one. Later he consents to spare them, but Prometheus must expiate his crime in bringing down fire from heaven, and it is this which forms the subject of the second play in the trilogy.

In one respect, the Prometheus Bound differs from all other plays; it makes no use of the stage, the action proceeding entirely on the balconies, where the scene represents a desolate and rocky region near the shore of Oceanus, or, as the Greeks supposed, at the end of the world. To the summit of a craggy mountain, Vulcan, attended by Strength and Force, is binding the arms of Prometheus with chains, driving an iron wedge through his breast, placing a girdle round his hips, and encircling his feet with fetters of brass. Then, after insulting him, they leave the god, thus imprisoned, alone with his pain. He is, of course, represented by a lay figure, so contrived that an actor, standing behind the pictorial mountain, could make himself heard through the mask.

Inexpressibly grand are the words in the original Greek, in which, when left alone, chained to a rock, Prometheus calls on air, winds, floods, sea, earth and sun to witness what he, a god, must suffer at the hands of the gods.

- Thou firmament of God, and swift-winged winds,

- Ye springs of rivers, and of ocean waves

- That smile innumerous! Mother of us all,

- O Earth, and Sun's all-seeing eye, behold,

- I pray, what I, a god, from gods endure.

- Behold in what foul case

- I for ten thousand years

- Shall struggle in my woe,

- In these unseemly chains.

- Such doom the new-made Monarch of the Blest hath now devised for me.

- Woe, woe! The present and the oncoming pang I wail, as I search out

- The place and hour when end of all these ills shall dawn on me at last.

- What say I? All too clearly I foresee

- The things that come, and nought of pain shall be

- By me unlooked-for; but I needs must bear

- My destiny as best I may, knowing well

- The might resistless of Necessity.

- And neither may I speak of this my fate,

- Nor hold my peace. For I, poor I, through giving

- Great gifts to mortal men, am prisoner made

- In these fast fetters; yea, in fennel stalk

- I snatched the hidden spring of stolen fire,

- Which is to men a teacher of all arts,

- Their chief resource. And now this penalty

- Of that offense I pay, fast riveted

- In chains beneath the open firmament.

- Ha! ha! What now?

- What sound, what odor floats invisibly?

- Is it of God or man, or blending both?

- And has one come to this remotest rock

- To look upon my woes? Or what will he?

- Behold me bound, a god to evil doomed,

- The foe of Zeus, and held

- In hatred by all gods

- Who tread the courts of Zeus;

- And this for my great love,

- Too great, for mortal man.

To the chorus of ocean nymphs, who, pitying his sad fate, approach him with kind intent, he tells the story of the offense for which he is being punished:

"When Chronos and Zeus were stirred up in mutual strife, I alone of the Titans took my side with Zeus. And by my counsels old Chronos is in the deep, dark pit of Tartarus, with his allies; and thus am I repaid. Then Zeus began to share his gifts among the gods, but of mortal men he took no heed, but rather was he purposed to crush out the race and make a new one. And none save me dared cross his will. But I did dare, and mortal men I saved from passing down to Hades, crushed with thunderbolts. I gave them hope, and so turned away their eyes from death, and I gave them fire, that thereby they might learn many arts. Wherefore these ills oppress me now, and I pine on this lone mountain, all neighborless. Helping men, I find no help myself, and but await yet greater evils."

The chorus grieves for his pain, and not alone, for all Asia echoes their moan and all the human race grieves in sympathy with his woes. One other, and only one, have they seen thus bowed in adamantine durance; Atlas, also a Titan and a god, who on his shoulders ever bears the mighty vault of heaven.

Extremely powerful is the scene where Hermes enters, as the messenger of Zeus, and haughtily bids him reveal the marriage--known only to Prometheus--which shall some day hurl Jove from his throne. Prometheus undauntedly replies that there is no torture nor device by which Zeus can compel him to reveal these things until his bonds are loosed. Then Hermes threatens him with greater sufferings:

- With thunder and the lightning's blazing flash

- The Father this ravine of rock shall crush,

- And shall they carcass hide, and stern embrace

- Of stony arms shall keep thee in thy place.

- And having traversed space of time full long,

- Thou shalt come back to the light, and then his hound,

- The wingéd hound of Zeus, the ravening eagle,

- Shall greedily make banquet of thy flesh,

- Coming all day an univited guest,

- And glut himself upon thy liver dark,

- And of that anguish look not for the end,

- Before some god shall come to bear thy woes,

- And choose to pass to Hades' sunless realm.

In vain the chorus counsels submission. Prometheus bids Hermes add torture to torture, "yet me he shall not slay." Then the threatened destruction begins.

- Yea, now in very deed,

- No more in word alone,

- The earth shakes to and fro,

- And the loud thunder's voice

- Bellows hard by, and blaze

- The flashing levin-fires;

- And tempests whirl the dust,

- And gusts of all wild winds

- On one another leap

- In dire, conflicting blasts,

- And sky and sea are bent.

- Such is the storm from Zeus

- That comes as working fear

- In terrors manifest.

- O mother venerable,

- O Æther, rolling round,

- The common light of all,

- Seest though what wrongs I bear?

With these lines, spoken by Prometheus as the chorus retires, the play concludes; the rocks fall asunder, and the victim is dashed down into Tartarus.

The Prometheus Bound is the representation of steadfast endurance under suffering, and, indeed, the immortal suffering of a god, banished to a desolate rock over against the earth-encircling ocean. This play nevertheless takes in the world, the Olympus of the gods, and earth the abode of man, all scarcely yet reposing in a state of security over the precipitous abyss of the dark primeval powers of Titanism. The notion of a deity delivering himself up as a sacrifice has been mysteriously inculcated in many religions, as a confused foreboding of the true one, but here it stands in most fearful contrast with consolatory revelation. For Prometheus suffers not on an understanding with the Power that rules the world, but in atonement for his rebellion against that power, and this rebellion consists in nothing else than his design of making man perfect. Thus he becomes a type of humanity itself, as, gifted with an unblessed foresight, riveted to its own narrow existence and destitute of all allies, it has nothing to oppose to the inexorable powers of nature arrayed against it, but an unshaken will and the consciousness of its own sublime pretensions.

Of exterior action there is little in this piece: from the commencement Prometheus suffers and resolves, he resolves and suffers the same throughout. But the poet has contrived in a most masterly manner to introduce vicissitude and progress into that which is irrevocably fixed, and to afford a measure of the unattainable grandeur of his sublime Titan in the circumstances which environ him. First, the silence of Prometheus during the horrible process of his fettering under the rude superintendence of Strength and Force, against whose menaces Vulcan, their instrument, can only offer an unprofitable compassion; then his lonely complainings; the arrival of the femininely tender Oceanides, amidst whose timid lamentations he gives more free vent to his character, recounts the causes of his fall, and prophesies of the future, which, however, with wise reserve, he but half reveals; then the visit of old Oceanus, a kindred god of Titanian extraction, who, under the show of wishing to be a zealous intercessor for him, counsels submission to Jupiter, and is therefore dismissed with proud disdain. Observe how Io, the frenzy-driven wanderer, comes before him, a victim to the same tyranny under which Prometheus lies subdued; how he prophesies to her of her yet impending wanderings, and of her final destiny, which hangs connected with his own, inasmuch as from her blood, after many generations, a savior shall arise to him; further how Hermes, as the messenger of the universal tyrant, with domineering menaces demands of him his secret, in what way Zeus is to be secured upon his throne against all the malice of Fate; how, at last, before the refusal is well-uttered, amidst thunder, lightning, storm and earthquake, Prometheus, together with the rock to which he is fettered, is swallowed down into the infernal world. The triumph of subjegation has, perhaps, never been more gloriously solemnized, and it is difficult to conceive how in Prometheus Unbound the poet could maintain his ground on an equal elevation.

Purchase Prometheus Bound

|

|

|

|

|